Forested areas provide multiple watershed benefits including capacity to retain precipitation and moderate flows. Protecting forested lands in the watershed may help your community avoid damaging peak flows. Communities can also look at amount of impervious surface in the watershed and find ways to reduce discharges from smaller storms through Low Impact Development designs and Green Infrastructure projects.

Links to sections below:

- What is a Watershed?

- How do Forests Reduce Flooding?

- Why is this Important?

- What is Stormwater?

- What is Impervious Surface?

- What Can Communities Do About Impervious Surface and Stormwater?

- How Much is Too Much?

- Managing Water from Impervious Landscape

- How Can We Protect Forests?

What is a Watershed?

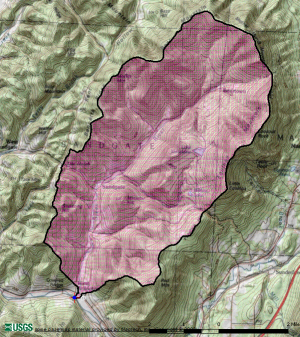

A watershed is the area uphill that drains to that place. The image here shows the watershed for the Green River as delineated by the USGS StreamStats website. The Green River drains thirty square miles and most of the Town of Sandgate. Near the Sewage Treatment Facility in Lyndonville, the Passumpsic River flows with water collected from nearly two hundred square miles of its watershed.

How do Forests Reduce Flooding?

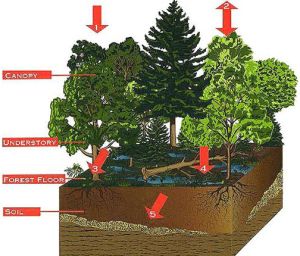

Forests have multiple benefits for watersheds including the moderation of water discharges.

Forests and Trees

- Intercept precipitation (and return it to the air directly);

- Detain rain and snow on and in accumulated leaves and branches;

- Allow snow to melt slowly in the shade;

- Promote infiltration of water into the soil and replenish groundwater;

- Release water into the air through leaves

The Vermont Urban and Community Forestry Program underscores the importance of protecting forests, enhancing the health and condition of forest fragments, and reforesting open land. In urban areas, the establishment of tree plantings can help moderate problems with water from storms.

Why is this Important?

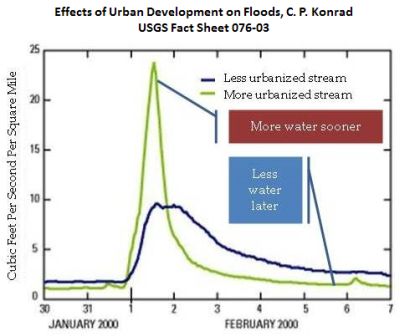

If water is not intercepted, retained and delayed in forest cover then more water may come sooner and quicker - exacerbating flash-flooding and erosive impact. Conversely, if the water all runs off quickly then less water will infiltrate to recharge ground water and get released over time to support critical low streamflows. The functions of forest cover can be expensive, if not impossible, to replace utilizing other methods.

The amazing difference in the state of a cultivated and uncultivated surface of erth, iz demonstrated by the number of small streems of water, which are dried up by cleering away forests. The quantity of water, falling upon the surface, may be the same; but when land iz cuverd with trees and leevs, it retains the water; when it iz cleered, the waters runs off suddenly into the large streems. It iz for this reezon that freshes [floods] in rivers hav becume larger, more frequent, sudden and destructive, than they were formerly. - Noah Webster, 17901

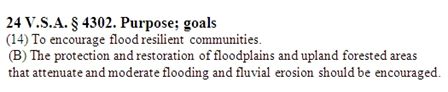

To become flood resilient Vermont Statute encourages communities and state agencies to protect and restore upland forested areas that attenuate and moderate flooding and fluvial erosion.

To become flood resilient Vermont Statute encourages communities and state agencies to protect and restore upland forested areas that attenuate and moderate flooding and fluvial erosion.

The protection of forests can be addressed through a range of initiatives including community assessments and planning, along with regulatory measures, non-regulatory incentives and partnership efforts.

Community Opportunities

- Identify the watersheds that affect your community.

- Where are the forests in your watersheds? What percent is not forested?

- What land uses are likely to increase over the next decade?

- Do you have data on the subdivision of forested parcels?

- Where are forests associated with high elevations, steep slopes, wetlands, riparian areas or other fragile and important areas?

- What can your community do to support existing forest cover, trees, and to limit the impact of hardened/ impermeable surfaces?

Thinking ahead and protecting critical areas can be the most valuable contribution a community can make in protecting its citizens from climate change effects. - Sandy Wilmot, Forest Health Specialist, Vermont Department of Forests, Parks & Recreation

What is Stormwater?

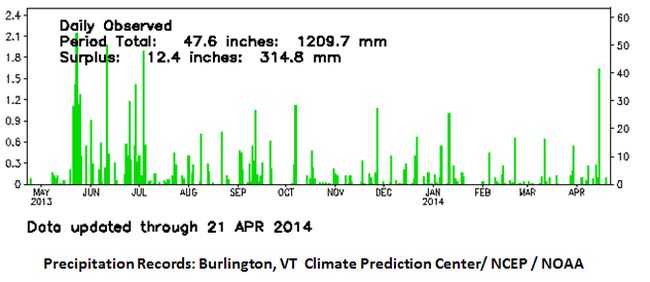

The water draining from even small precipitation events can cause significant problems.

The water draining from even small precipitation events can cause significant problems.

The effect of a half inch of rain rinsing parking lots and roads can send a slug of warm polluted water into nearby streams and ponds. When the community has a lot of hardened/ impervious surface more water arrives more quickly into the stream gouging out the channel and moving more sediment and phosphorus downstream. Sooner and faster water is also more likely to overwhelm storm drains, blow out culverts and in some places overwhelm the sewage treatment plant.

By managing impervious surface and not speeding the discharge of water into streams and municipal systems, the community can avoid a lot of misery, damage and expense.

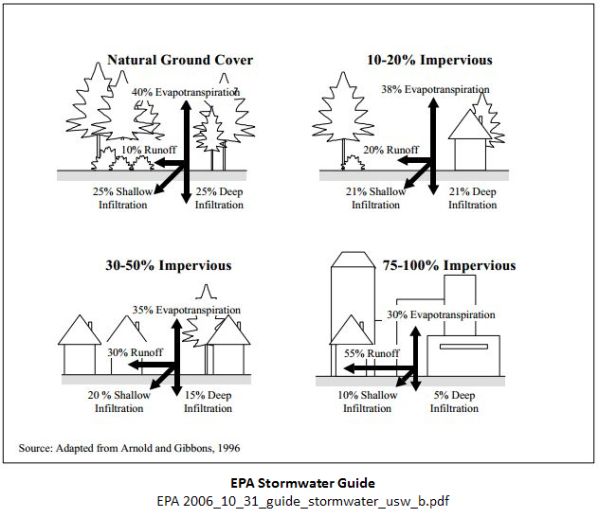

What is Impervious Surface?

Impervious surface does not allow water to soak into the soil where it falls. When water is displaced from one spot and rapidly sent somewhere else the next place may also become overwhelmed. Some landscapes readily soak up a lot of water (particularly sandy soils). Clay soils on the other hand are slow to wet, slow to dry and do not pass water easily. Places where the slope is steep or the soil is shallow to rock can also get overwhelmed. As people change the landscape the increase in impervious surface in one location (roofs, driveways, roads and parking lots) may cause damage down the hill. It is possible to take steps to avoid this problem going forward. It is also possible to fix the problem where it already occurs, but that may become increasingly expensive.

What Can Communities Do About Impervious Surface and Stormwater?

- Be aware of the percentage of impervious surface you have in the watershed. See USGS StreamStats.

- Avoid more off-site discharges of stormwater by adopting Low Impact Development (LID) Standards. This would require each landscape change to not release the stormwater off site in a way that would impair other existing or future uses.

- Reduce current problems from stormwater discharges by implementing Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) methods.

- In severe situations gray infrastructure (concrete) designs may be needed. But even these can be created to be attractive and meet other community goals.

- Some communities have streams and lakes that have already become impaired by stormwater. These communities can prepare a comprehensive stormwater plan and develop systems such as stormwater utilities to help fund and correct the established problem.

How Much is Too Much?

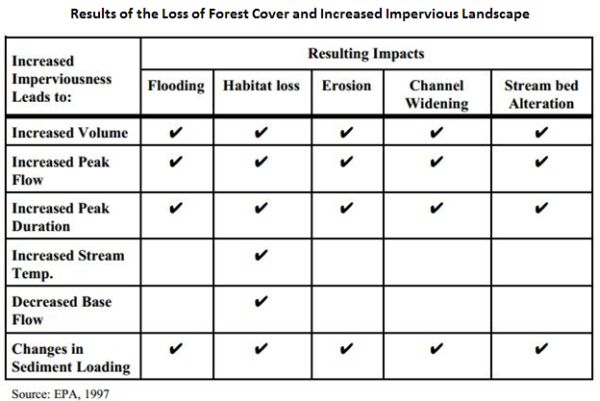

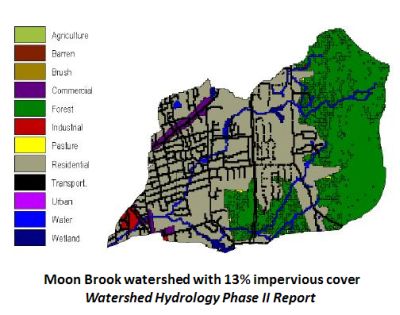

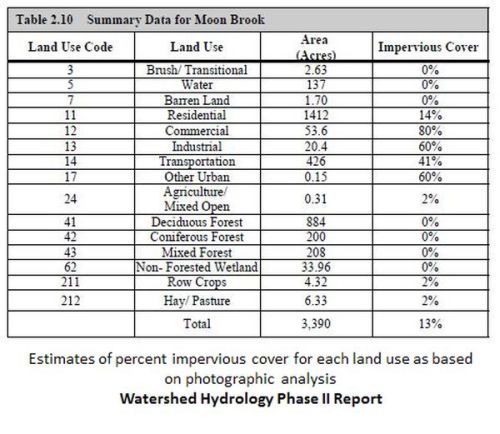

Forest cover is one of the most water-retaining land uses. Wetlands also have capacity to detain significant amounts of water. In more developed “urbanized” landscapes there are more surfaces that do not absorb and detain water such as roofs, roads, parking lots and driveways. As the watershed becomes more urbanized the peak flows become higher and more frequent. Urbanization can amplify flood levels and erosive power and drive channel scouring, habitat degradation, and water pollution.

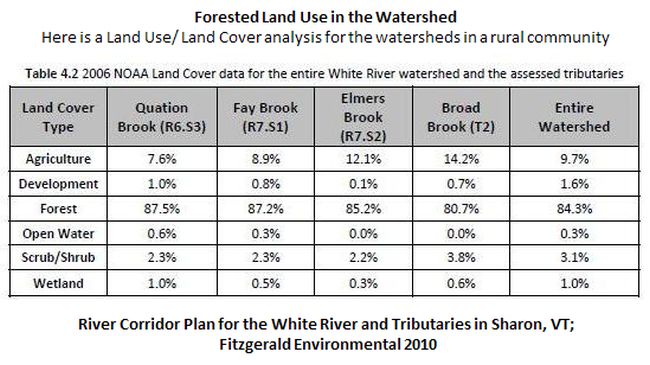

Forests in the watershed and even individual trees can help temper peak flows from small storms and larger events. Forests, particularly on higher and steeper locations, provide self-renewing areas that retain and delay water and reduce sediment loading. Branches and trees in the stream channel slow waters, and trap sediment appropriate to an equilibrium condition. It is possible to examine the existing land cover in a watershed and to describe how impervious the area is. Ideally you should be able to anticipate and see changes over time but the current map data for Land Use / Land Cover is still fairly limited.

Your Regional Planning Commission may be able to help describe the land use/ land covers in your key watersheds.

The Vermont Natural Resource Atlas has useful data identifying:

- Watershed Boundary Dataset

- (Forested) Habitat Blocks

- Vermont Significant Wetlands Inventory (VSWI), and

- Percent Impervious Surface

You can also use the USGS Vermont StreamStats website to delineate a watershed for any stream in Vermont and generate information about the size of the watershed, percentage of impervious surface and flood discharges.

The VT River Corridor Planning Guide identifies possible hydrologic stressors on river corridors including deforestation; urban land use; stormwater inputs; diversions, dams, and dam operations; wetland loss; and road and ditch networks.

Altered hydrology may be a significant stressor when urban land use reaches 5-10% of the watershed (depending on the percentage of the urban land use that is actually impervious cover) and may be the predominant stressor when it reaches 20% of the watershed.

Watershed Hydrology Protection and Flood Mitigation Project Phase II - Technical Analysis Stream Geomorphic Assessment Sept. 1999, Stone Environmental for Vermont Geological Survey.

Mapping Impervious Surfaces in the Lake Champlain Basin October 2013 Final Report Prepared by: Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne, University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Laboratory for: The Lake Champlain Basin Program and New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission

Watershed Hydrology Protection And Flood Mitigation Project Phase II - Technical Analysis Stream Geomorphic Assessment Final Report 9/1999 by Center for Watershed Protection, Ellicott City, Maryland for Vermont Geological Survey

- What are the forest land cover and permeability conditions in your watersheds?

- How are forests and permeability changing?

- Where are forest blocks with multiple values including flood resilience?

- How can the community connect forest owners and community organizations to protect forests and their watershed functions?

- Do the plans and regulations in your community discourage the fragmentation and loss of forest resources?

- Does your community direct future growth to locations that minimize the loss of forest resources and their watershed services?

Resources on Urbanizing Watersheds and Increasing Peak Flows

Effects of Urban Development on Floods, C. P. Konrad, USGS Fact Sheet 076-03

Urbanization and Streams: Studies of Hydrologic Impacts EPA

Case Studies - impacts that increased flow due to urbanization - EPA

VT ANR River Corridor Planning Guide April 1, 2010

Managing Water from Impervious Landscape

As land becomes developed it is possible to mitigate some of the impact on permeability and avoid higher stormwater and flood discharges by:

- Protecting existing forests and woodlands

- Adopting Low Impact Development standards (LID), and by

- Implementing Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) steps to respond to existing problems.

Low Impact Development refers to an approach to land planning and site design that tries to prevent and minimize environmental degradation. GSI, on the other hand, refers to and relies on the physical elements (natural or man-made) of the landscape when addressing or minimizing impacts from stormwater runoff. In other words, LID is a series of planning principles and GSI is a set of physical best management practices.

Low Impact Development: Planning and Policy

VLCT Model Low Impact Development (LID) Bylaws

Low Impact Development Review Checklist – Guilford, Connecticut

Green Infrastructure Initiative YouTube Channel

Road surfaces and road drainage can also make large contributions to stormwater flows, sediment and erosive power. Has your town conducted a Better Back Roads assessment to identify roads that direct significant volumes of water and sediment to streams during rain storms?

How Can We Protect Forests?

Where your community has forest resources established in important watersheds these help protect those sites and communities downstream in the watershed. Where forests have been reduced to a smaller percentage of the area in the watershed, their watershed services may be expensive to replace.

Forests may be recognized in your municipal plan for multiple values. All of these may be important to the community's work to protect the watershed functions of forests.

Here are some useful resources and links:

The Role of Trees and Forests in Healthy Watersheds: Managing Stormwater, Reducing Flooding, and Improving Water Quality, Penn State Extension

Community Strategies for Vermont’s Forests and Wildlife: A Guide for Local Action, VNRC 8/2013

The Place You Call Home, Northern Woodlands

Vermont Urban and Community Forestry Program

- Water Quality and Stormwater

- Forests, Trees and Water

- Trees and Stormwater

- Main Streets to Green Streets

- Forest Water Quality Program – Vermont Division of Forestry

- Vermont Urban and Community Forestry Program (VUCF Program) and Contacts

- Community Forestry Program Resources - VUCF Program

- Grants – Urban and Community Forestry Program – VUCF

1Noah Webster A Collection of Essays and Fugitive Writings on Moral, Political, and Literary Subjects (Boston 1790) as quoted by William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England 1983